The Destruction of Ke’ér

Beyond the front cover, bearing a full-color illustration by M.A.R. Barker himself, we are met with a poem written in Tsolyáni, one of the many langues constructed for the fictional setting.

Be prepared to drink heavily from the firehose of lore, something that is a requisite for consuming information on Tékumel.

We are provided a summary of this text: a Tsolyáni general named Bazhán assaults a fortress after the attendant refused to surrender. The woman who refused surrender, Yilrána was impaled - which we are told is a Tolsyáni custom. This destruction is later witnessed by her partner, the Baron of Yán Kór when he arrives later with reinforcements.

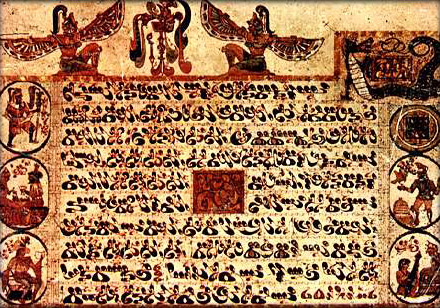

The Tolsyáni script has both pronunciation and its translation to English below it. The book requests no reproduction of the text be made, so I will honor that request and not post the poem, but here is an image from Dragon Magazine Vol. 1 #4 depicting some of the script:

The poem is signed Fíru Bá Yéker on the 23rd of Fésru 2.333 A.S. - whatever that means

So we get some details. There’s Barons and fortresses, mistresses and generals. We are also introduced to the notion that this world has traditions, albeit a brutal and violent one, but we already see that there is culture to this world.

It may be worth a detour to understand a little more about our author, and why the first thing we are met with is a constructed language.

The Professor

M.A.R. Barker was a very interesting figure - born as Phil Barker in November 2nd, 1929 in Tacoma Washington he was reported to have been enamored by languages and history at an early age. Egyptian and Mayan are a cited interest, in addition to science fiction, he started constructing a “play world” very early, one in which he carved toys for bearing resemblance to these influences.

He attended the University of Washington at Seattle, graduating Magnum cum laude with a Bachelor of Arts in Anthropology in 1951. After which he was awarded a Fullbright scholarship to study abroad in India, continuing his pursuit of anthropology he performed field work studying the wide variety of tribal dialects. During this time he converted to Islam and changed his name to Muhammad Abd-al-Rahman Barker.

Continuing to study on his return to the United States, Barker worked on a Nahuatl dictionary, and would go on to attend University of California Berkley to study linguistics, performing research on the Klamath language. Around this time (mid to late 1950s) he would facilitate fictional games in his imagined world of Tékumel, long before the publication of Dungeons & Dragons. This seems to indicate that his constructed languages were already presentable, as they appeared on in-fiction documents presented to the players.

In 1957 he was hired by McGill Institute to teach Islamic Studies and Arabic, and there he wrapped up his dissertation on Klamath. Two years later he was teaching Linguistics as well as Baluchi, Brahui, Panjabi, Pashto, and Urdu at the Oriental College of Lahore, West Pakistan. He even published a book of poetry written in Urdu.

He would continue teaching, studying, and traveling the world with his wife Ambereen for years. In 1972 he became the head of South & Southwest Asian Studies at the University of Minnesota, and through the wargaming club there he would eventually be introduced to Dungeons & Dragons by Mike Mornard (the person who coined the term “FKR”, coincidentally) and would start work on the game we are reading.

Obviously this is not an exhaustive biography, but I wanted to point out the Professor’s love of languages and call to attention many likely influences, as well as to provide context as to why we start with some fantasy linguistics.

Tsolyáni

The Tsolyáni constructed language is the most detailed fictional language in Tékumel, although there are several more. It may have also been the first conlang to appear in gaming material, although I wouldn’t be surprised if one of Tolkein’s languages slipped into a wargame earlier. One could feasibly study this language, were one so inclined: The Tsolyáni Language.

Tékumel’s communities seem torn about how into these languages one should get. I personally think if its a draw to you, dive right in, but I don’t blame anyone for raising an eyebrow at all the in-fiction terminology and proper nouns.

That said, I love this kind of stuff. I know it hasn’t been in vogue since like the 90s to do in world fiction, but I think when done well, and with such a beautiful script it immediately puts me in the mind of “ok, imagination time.”

In reference the topic on Running Unique Settings this is certainly one avenue a referee can take. Obviously this won’t fly with every player, but those that are into this - this sort of stuff can go a long way.

Wrapping Up the Inside Cover

Ok this was a little longer than I expected. Let me know your thoughts on this page (if you’ve read it), conlangs in fantasy and science fiction generally, Áll Thé Áccént Márks. As well as any additional information about Prof. Barker you wanna discuss, especially any corrections. @VanWinkle keep me honest please!

Next time let’s see what two guys named Gary and Dave have to say about all this.