A conversation came up in the Discord (in the Storygames channel) asking about how to add more character-driven play to a game. There was some advice given to add in mechanics like Keys (from The Shadow of Yesterday) or other incentivizing mechanics, and someone suggested that these mechanics might provide good support (kind of like training wheels) to get people used to this kind of play.

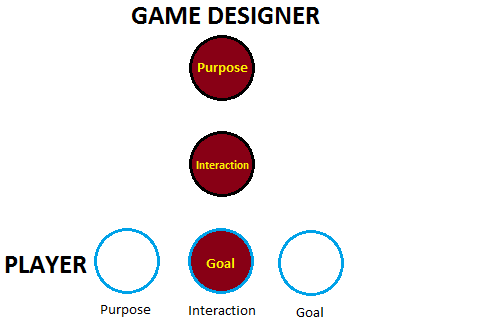

I see it a little differently: rather than being training wheels, I’ve found that these kinds of mechanics are often distractions and lead people new to this kind of gaming away from the things that are necessary to achieve it consistently. While mechanics like Keys from The Shadow of Yesterday can indeed support/energize thematically-rich, character-driven play, in games where they do so effectively, they aren’t doing it in a vacuum. There are three necessary elements for this kind of play: if you have them you don’t need mechanics like Keys. If you don’t have them, mechanics like Keys won’t get you there — they can’t create them for you.

By “mechanics like Keys” here and throughout, I’m talking about mechanics that give a certain amount of XP or some kind of bonus for bringing out a specific trait, characteristic, or thematic issue of the character. That is: mechanics that try to incentivize characterization. I’m not talking about things like Psychological Disadvantages in early Champions, which provide guidelines towards/constraints on characterization but aren’t connected to an incentive. Nor am I talking about what we see in games like The Pool or Hero Wars (1st edition of Heroquest) where there’s a fee form trait system, some of which might be “characterization-focused” (“wants revenge on the Baron +1”) but which are mechanically identical to all the other kinds of abilities (“has a big sword *1”).

Ok - here are the three necessary elements.

First, you need the situation to be one that we as people sitting around the table find genuinely interesting on a human level. Not something that reminds us of stories from other media, not something that recycles gamer tropes (so no wizard who gives us a quest with a plan for him to later backstab us). Rather, something that engages us in some kind of dilemma that each of us, as an individual, could be expected to have a different take on.

As an example from a recent game of mine: one of the PCs’ allies had broken a taboo (for some understandable if not completely justifiable reasons) and brought down a curse on the community. The PCs needed to work out how to handle the situation given a number of competing factors: this was their ally who had fought side by side with them in the past, he definitely did step out of line and in doing so brought consequences down on otherwise innocent people, and his reasons for breaking the taboo were sympathetic and paralleled the motivations of some of the PCs. The one clear way to reverse the curse was to make sure their ally was punished — but that wasn’t something any of the PCs could take on lightly.

I bring this example up not because I think it is especially creative or imaginative: rather it is pretty basic — but it more than meets the necessary criteria of being a situation where different PCs — and different players — could have equally valid yet differing opinions on how to resolve it.

(Jesse Burneko’s Dungeons & Dilemmas offers a great procedure for developing these kinds of situations for dungeon-crawl based games).

Second, you need procedures to resolve uncertainties that result in consequential changes to the immediate situation and where outcomes — especially unwanted outcomes — cannot be undermined or massaged out of existence. Luckily, we have no shortage of these kinds of procedures from the beginning of role-playing onwards, although we have to approach them without a lot of the well-meaning “GMing advice” that effectively nerfs (softens or subverts) otherwise solid resolution procedures. We — all of us, GM and players — need to be willing to honor those outcomes and recognize that it is not the GM’s responsibility to shape them or make them more palatable.

Third, and this follows directly from the above: we need to honor player choices so that when they decide what their character’s attitude towards or opinion about the situation is and then decide on how to act on that opinion, we let that action proceed through the resolution procedures, without deflection and without requiring some kind of table consensus about a given character’s actions. This means, among other things, throwing away the idea of “the party” — the implicit or explicit idea that the characters are really one big character (I’ve heard this described as a kind of Swiss Army Knife approach) and that their actions can only proceed once there is consensus among the players. (Note: the Swiss Army Knife approach is perfectly suitable for lots of challenge-based gaming but will completely subvert character—driven thematic play).

Here’s how these things work together to allow for thematically-rich character-driven play:

The situation is a moral/ethical dilemma with thematic potential. It is the thematic equivalent of a well-designed battlemap that forces interesting (tough) tactical choices on us. There is no one “right” way to approach it: because of that, players have the opportunity to have their characters take actions which express the individual character’s full emotional, psychological, and moral response to the situation.

And we allow the players to take these actions that express those responses: we don’t try to artificially or coercively form a consensus or force the actions down a path based on our familiarity with genre conventions from other stories.

Finally, when we make use of the procedures for resolving uncertainty, we end up with a situation that has been irreversibly and meaningfully changed by the actions taken by the player characters. We now know something about these characters that we didn’t know before — what they believe, what they are willing (or not willing) to do for their beliefs, how they deal with the consequences of those actions, etc.

We didn’t need any specific mechanics incentivizing characterization or character motivation to get there. We got there because doing this activity is fun, enjoyable, and compelling in its own right.