This is a great set of questions and bound to give rise to much discussion here, especially as so many house-rule-makers and designers hang around here.

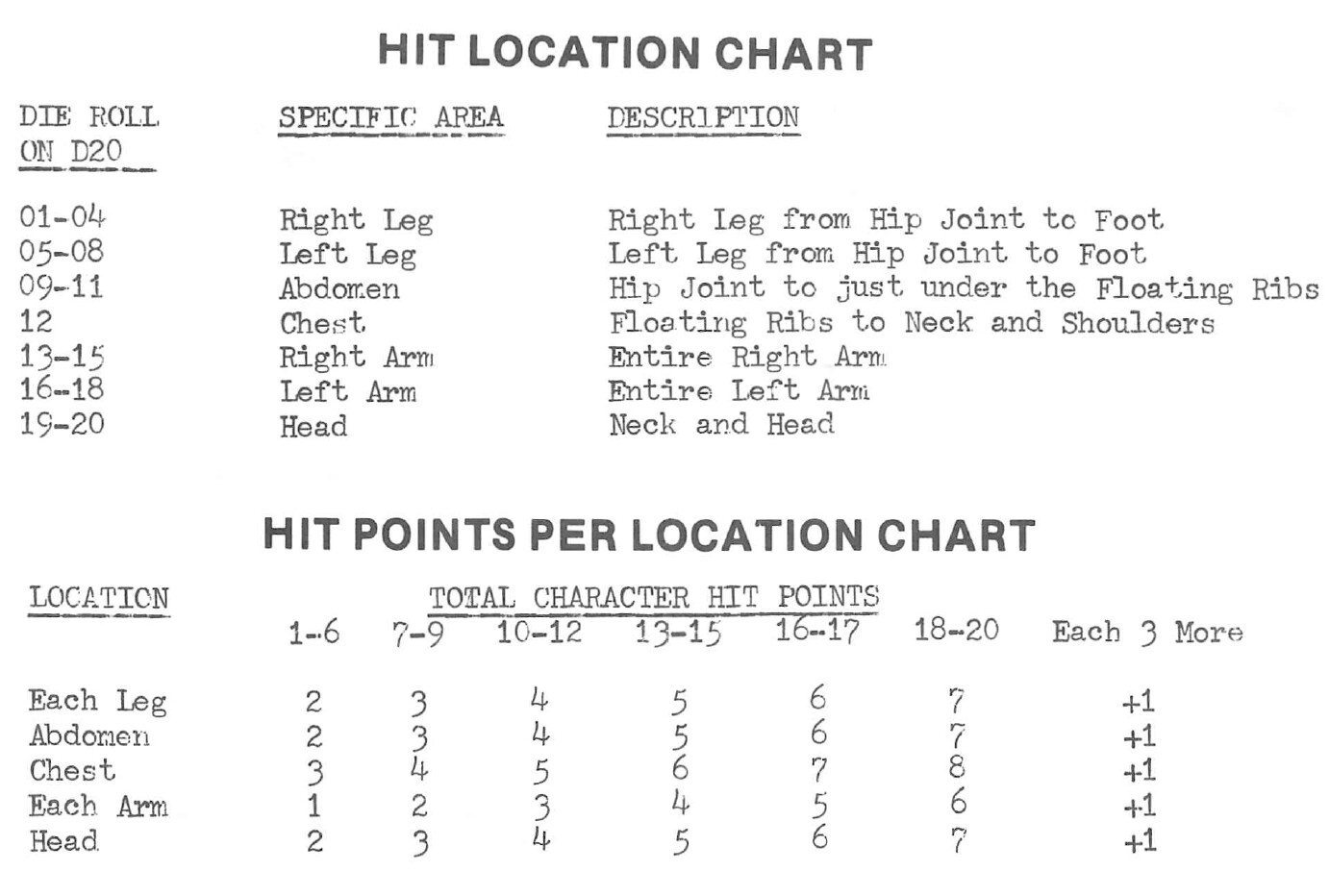

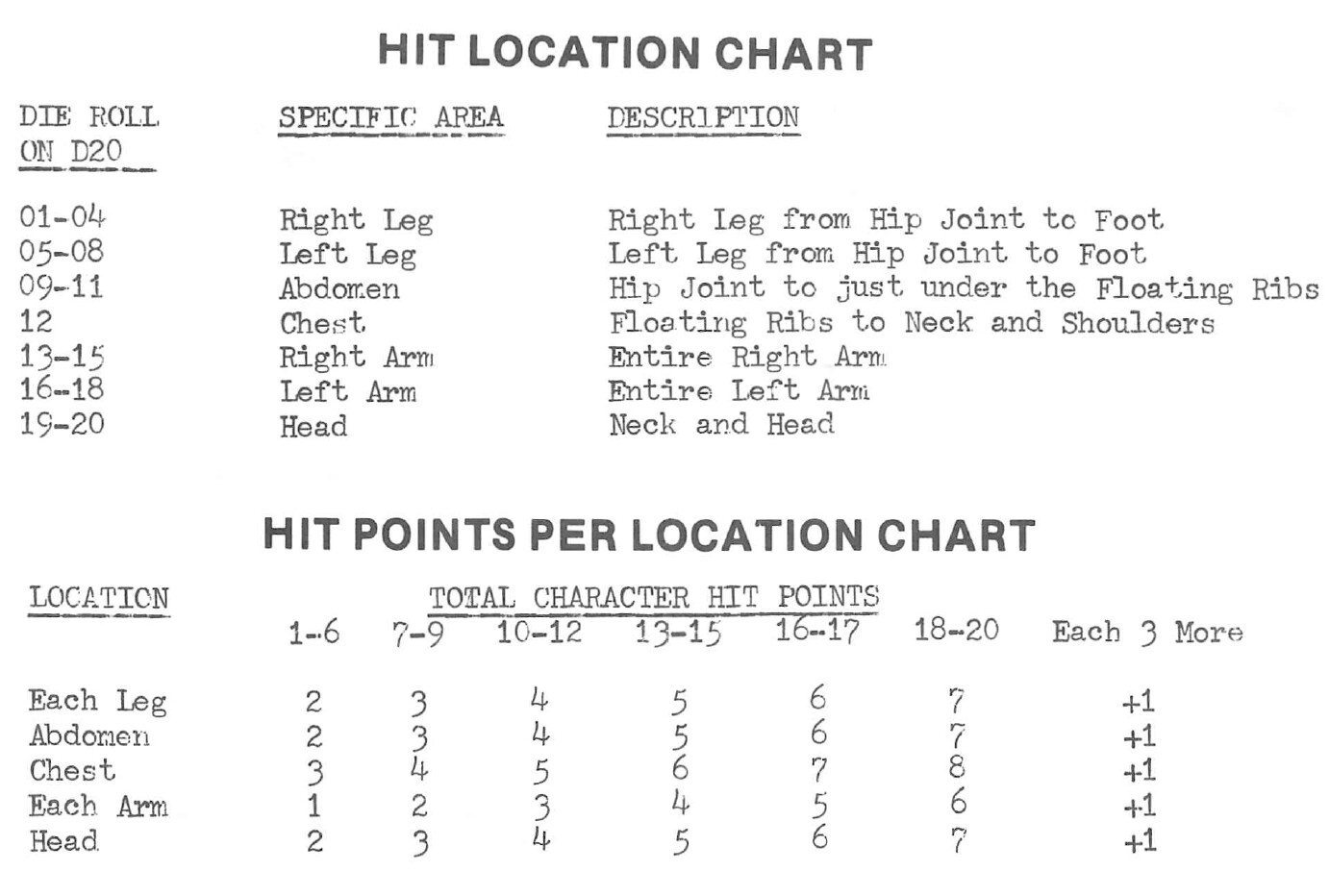

I want to mention is that this is an old debate. The early instinctive reaction to D&D was to make more and more systems for things to which our attention should be drawn. This was to achieve a sort of realism within fantasy and also to allow characters more rules-defined differentiation (rather than “just another third-level thief”). So, for example, Chivalry & Sorcery (1977) went for an idea of “completeness” (assuming that everybody was trying to do an “authentic medieval” fantasy) by piling on rules for social class and “authentic” magic and, generally, more things to keep track of. That way of doing things built up for a while. I still have a soft spot for the arcane rules of Aftermath (1981) and Powers & Perils. In the latter, for example, every PC requires a certain number of Food Points per day, depending on the character’s stats, and each food item is worth a certain number of food points for the one who consumes it. Hit locations, which you brought up, were in RuneQuest early on (1978).

Although RuneQuest has always had a following, the others I just mentioned were failures with respect to audience size. I’d peg that on their complexity.

I think the problem was that complexity just to be “complete” is a serious distraction from play. Instead, people should make a system for stuff that matters in the world or genre. For example, Call of Cthulhu wouldn’t be the same without the Sanity rules.

So, partly it depends on what things need to be tracked to simulate the kinds of attention that the genre requires. Genre, which is comprised of shared expectations, is the common ground for everything.

I have come to think that a lot of the complexity that we have in games came to be specifically to allow statted-out advancement, instead of narrative advancement. It’s as if designers made more stats just to give room for regulated, tracked advancement, in the tradition of experience points.

Speaking for myself, after my return to gaming, I have far more sympathy for systems that are descriptive rather than numerical. Narrative complexity and narrative advancement don’t require numerical stats, but they do require memory or records of events.

What are all the numbers for? They establish points of agreement resistant to interpretation and easily rendered into factors for dice odds, so that players and referees don’t disagree about what’s possible. By that measure, the more agreement there is about genre and expectations between participants, the less rules-and-numbers complexity is required.

With that in mind, I think that rules complexity and stat counting facilitate (1) methods of advancement and (2) play between strangers (who may not have established genre expectations), but whatever gains stat complexity offers are mitigated because (a) complexity also hinders newcomers and (b) players who play with each other for a while cease to be strangers and feel out genre expectations with one another.