I think it’s important to mention that the Hex-Crawl/Point-Crawl approaches aren’t mutually exclusive: Both methods provide different benefits/drawbacks and they can also work in conjunction with each other.

I like Hex Maps to provide me, as a Referee, with that “Bird’s Eye View.” They can help me understand the Biomes/Terrain/Environments being explored, and the Relationships of Important Features with each other. The Hexes can serve as Containers for Stocking Purposes, identify specific Regions that share Encounter Tables/other Features, or work like “Rulers” for me to quickly adjudicate/estimate Distances/Time for providing things like Directions or Rumors.

The Hex Map in my games isn’t really Player Facing though, it’s just a tool for me to help adjudicate that Overland Travel. Players might receive or acquire more “In World” Maps, but I don’t really portray the Wilderness to them in terms of those “Hexes.” Providing the Hexes can sometimes influence decision making in strange ways I’ve found: Many Players assume that once a Hex is “Traversed” it’s been dealt with, or they may use it to directly gauge Decision making like Supply Requirements/Travel Times…taking some of the Mystery and sense of Adventure out of Wilderness Exploration and Discovery.

Travel Overland is always going to take place on Paths of some sort: You don’t walk directly through a Lake without the aid of Magic, so you circumnavigate via the Shoreline. A Formidable Mountain Range might require locating a suitable Pass or Switchbacks. The key thing I try to remind myself about is that Travel is seldom in those straight-lines as the Gryphon flies. Even Roads/Rivers can wind and wend. These can either be explicitly mapped out or handled more abstractly. With the Wilderness Exploration Procedures I tend to use, we don’t usually try to granularly represent every footfall or moment of Travel. We focus more on the Decision Points/Choices, Encounters, and Features/Discoveries made along the way. In some ways these are a bit like the “Points” in a Point-Crawl.

In terms of “Stocking” Hexes I do have a document that explains my Process Hex Stocking Example that includes some examples and links to several of my Resources. When it comes to Placing a pre-existing Module/Dungeon within, I simply choose a suitable location based on the Terrain/Surrounds usually. If the Module references a Settlement, I might substitute that or place it on the Map as well.

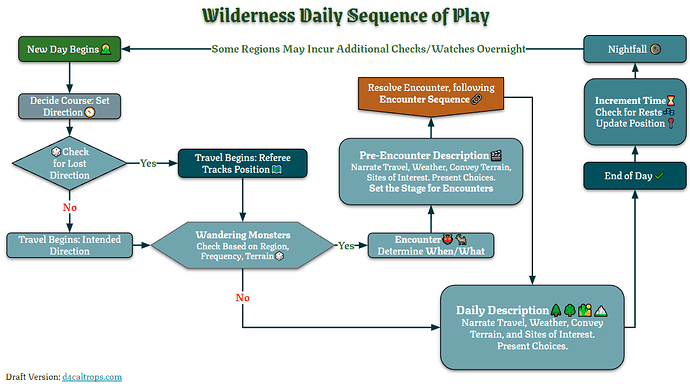

Wilderness Exploration does benefit a bit from Procedures I’ve found: Random Encounter Frequency is part of this. The Basic “B/X Framework” is a pretty good skeleton for this to flesh-out:

You may find that you want to handle things at a different level of granularity (Watches instead of Days, Weeks instead for longer journeys, etc.) but the basic framework helps insure that none of the necessary “steps” are skipped, Procedural Checks are made as appropriate, and Resource Depletion isn’t overlooked.